Sunday, October 05, 2008

Asking for Mechilah

Friday, September 21, 2007

Trembling

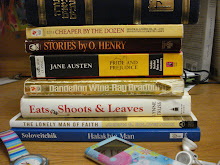

One thought on Yom Kippur, that I heard from Rabbi Hanoch Teller during my year in Israel: people often complain that it is impossible to focus on tefillah while fasting. How are we supposed to concentrate our thoughts to heaven if our stomachs are rumbling? Rabbi Teller counters: haven't you ever been reading, and been so engrossed in the book that the hours fly by, until you finish, only to realize that your neck is sore, that it is 3:00 am, and that you are super hungry? (I, for one, know that this has happened to me.) It is possible to get so engrossed in a task that everything else gets shut out, even basic physical concerns. If we were able to immerse ourselves entirely in our tefillos, we would not even notice our hunger. Though very few people are actually on that level, even I have experienced it to some degree, if only for moments instead of hours. So on Yom Kippur, when my stomach starts to distract me, I redouble my efforts to focus on what I am saying, on what weighs in the balance and what I am asking for.

I wish everyone a gmar chasimah tova--may your tefilos be answered, and may we all be sealed for another year of life and happiness.

Friday, October 06, 2006

Has this happened to anyone else?

Only four days after Yom Kippur, I did something that I had resolved wouldn’t happen again (in this case, I’m talking about a ben adam l’chavero). When I resolved not to do it again, I really meant it. I really wanted it never to happen. But a part of me sort of knew it would, no matter how hard I tried (like when we all resolve never to speak another word of Lashon Hara, and mean it, yet know that we’ll probably slip up again at some point). But I didn’t think I’d mess up again so soon! I just have this sunken feeling, like I really let myself down (as well as the other person involved). How I am supposed to get back that confidence I had in myself? The belief that I really could improve, that I really would avoid the pitfalls of last year? Though what I did wasn’t a HUGE deal by the world’s standards perhaps, it meant a lot to me, and has really made me feel discouraged. I have an inclination to just hate myself for this, but I also know that that is not a productive attitude—in order to change, I have to believe that I am a strong enough person to change, that I really have it in me. It’s Erev Sukkot, and already I feel like I don’t have a clean slate. I don’t want to go into the chag feeling like this. I guess this is an attempt to improve my state of mind by expressing myself. Even though I fell down, I can get up again, and I will. I will resolve anew, and daven that both Hashem and the person I hurt will forgive my mistake, yet again. To anyone else who might be in a similar situation: don’t give up on yourself—just try again, and try harder! May the New Year bring continued growth and perseverance in the face of all challenges!

Ack Yom Tov is in two hours! What am I doing here? I’ve got to run! Chag Sameach!

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Teshuva

For obvious reasons, this topic has been cropping up a lot lately. Though Yom Kippur is over, some random thoughts about teshuva:

I had a discussion over shabbos about the hardest part of teshuva. We concluded that the hardest part is also one of the most integral components of ensuring that the chayt doesn’t occur again. When a person sins, it is usually not merely for the thrill of sinning, not done simply to rebel against G-d (if it is, you have a much bigger problem). Usually, a sin is done because a person believes that it will benefit him in some way. For example, you steal an i-pod because you want to enjoy use of that i-pod. Or, you embarrass your friend because in some way that makes you feel superior. So the issue is this: how do you retroactively get rid of the pleasure that you got from your sin? How do you force yourself to realize that in reality you did not benefit at all—that in fact, you lost exponentially more than you gained? Though you may have returned the i-pod or apologized to your friend, you still have a memory of the enjoyment that you got from the sin. How do you change that memory from a pleasant one to one that repulses you at the very thought? If a person is successful in this area, I think it is virtually certain that the sin will not occur again, because it means that he has realized that there is nothing to gain from the sin, and everything to lose. But unfortunately, it is really hard to do. Any suggestions about how to accomplish this feat?

This topic also leads in to another discussion that I had on shabbos at the residence of a very illustrious j-blogger (who I was privileged to finally meet properly). The question was raised: would it be a good thing if, as part of the teshuva process, the memory of your sin would be erased? After confessing your sin and thoroughly regretting it, all memory that the sin occurred would disappear. On one hand, this would be a solution to the problem I described above—if you have no memory of the sin, you can’t remember the pleasure you got from it. Yet, I argued that overall it would not be a good thing. If you have no recollection of your sin and your consequent regret, what’s to keep you from repeating your mistake? The fact that you sinned in a specific area must mean that you have a yetzer hara for that sin—that for some reason you are compelled to do it. The thing that will keep you from doing it again is the memory that you tried it, and then realized how wrong it was—and that it was eminently not worth it. Without memory, you have no experience to learn from, so you will just keep falling into the same traps.