....

Showing posts with label prayer. Show all posts

Showing posts with label prayer. Show all posts

Sunday, September 28, 2008

Standing Still

Somehow, the weeks leading up to Rosh Hashana are never enough time to prepare, never enough time to learn, to introspect, to create the right mindset for Yom Hadin. And suddenly, it is almost erev Rosh Hashana, and that fear steals over my heart, the fear that is mixed with awe, a sense of my own smallness in relation to the Infinity I will be addressing in just a few short hours.

Monday, September 01, 2008

Feeling Thankful?

Rosh Chodesh Elul not only ushers in a period of intense introspection, but also offers two chances to say Hallel, a tefillah of thanksgiving and praise. In conjunction with these themes I’ve been thinking about the emotion of thankfulness.

I know that I am as blessed as any human being could hope to be. I have a wonderful family and amazing friends. All of my material needs are consistently met and exceeded. I am in good health. I have been given gifts and talents to utilize in this world, as well as the opportunity to foster them. Very few people can count themselves more fortunate than I.

Yet, as I think about these blessings, I became conscious of how rarely I actually feel the emotion of thankfulness. Intellectually, I am constantly reminded of the fact that I should be thankful. I know that God has given me far more than I deserve, and I make sure to tell myself so at regular intervals. However, this is not the same as feeling thankful to God.

I realized that the only times that I am able to feel an overwhelming thankfulness to God are when I either acquire a new gift or nearly lose one that I have.

In the past, when I have been blessed with something that I had heretofore lacked, I have felt—combined with the happiness of the new blessing—a consuming thankfulness. It is hard to describe what it feels like; the emotion is euphoric and transcendent, and humbling to an extreme. Yet, almost inevitably, over time the emotion dulls and fades, as the new gift is assimilated into my frame of being.

Confronting the possibility of losing something also engenders in me an emotion of thankfulness. When a gift teeters in the balance, or seems to for a time, fear and prayer are my immediate reactions. If the gift is spared, my relief mingles with thankfulness to God, creating an emotional state that is generally even more intense than my thankfulness for a new blessing.

However, I have been unable to manufacture any passable facsimile of this emotion in my day-to-day life. I can remind myself that I should, and must, be thankful, but this is an intellectual knowledge, not an emotional one.

When a person does something for me it is easier to feel thankful. I am able to relate to a fellow human being, to visualize myself as the other and recognize the effort that the person has put in, with the knowledge that what the person has done for me was not required. I can imagine what it would be like to be the giver; I know that the gift I was given was inconvenient, or time-consuming, or difficult to give.

With God, it is not so. I cannot put myself in His position. I cannot imagine any “effort” on His part. There is a total disconnect between the state of the giver and the state of the receiver, making it far more difficult to create an emotion of thankfulness.

It is also easier to express gratitude to human beings. When a person goes out of his/her way to do something for you, even just a verbal expression of thanks can have a profound effect on both the giver and the receiver. Often, some sort of reciprocal act also communicates one’s appreciation. The very process of acting allows the receiver to internalize his gratitude.

With God, however, it is different. Yes, in the time of the BHMK there were (and will be, according to many opinions) korbanot, particularly the korban Todah, an active manifestation of thanks. And nowadays there are the hoda’ah sections of tefillah, verbal declarations of thanks for our blessings and the miracles that God performs for us daily. But although saying these prayers can sometimes have a minimal positive effect on my emotional state, it rarely creates the powerful emotion that I seek.

When dealing with God, my thanks can receive no tangible reception; I can see no effect of my words, and I know that my expression of gratitude cannot benefit the subject of it. In this case, the only entity who truly benefits is myself. This makes the thanks I utter echo endlessly in my own ears, yet still it rings hollow.

I do not know the solution to my problem. I do not know how to inspire or create an emotion of thankfulness to permeate my everyday life. I know only that I should feel thankful, that I want to feel thankful, and that, in the core of my being, I am thankful. I only hope that I can find a way to tap into some hidden reserve of emotion that will allow me to experience thankfulness in a way that is conscious and true.

I know that I am as blessed as any human being could hope to be. I have a wonderful family and amazing friends. All of my material needs are consistently met and exceeded. I am in good health. I have been given gifts and talents to utilize in this world, as well as the opportunity to foster them. Very few people can count themselves more fortunate than I.

Yet, as I think about these blessings, I became conscious of how rarely I actually feel the emotion of thankfulness. Intellectually, I am constantly reminded of the fact that I should be thankful. I know that God has given me far more than I deserve, and I make sure to tell myself so at regular intervals. However, this is not the same as feeling thankful to God.

I realized that the only times that I am able to feel an overwhelming thankfulness to God are when I either acquire a new gift or nearly lose one that I have.

In the past, when I have been blessed with something that I had heretofore lacked, I have felt—combined with the happiness of the new blessing—a consuming thankfulness. It is hard to describe what it feels like; the emotion is euphoric and transcendent, and humbling to an extreme. Yet, almost inevitably, over time the emotion dulls and fades, as the new gift is assimilated into my frame of being.

Confronting the possibility of losing something also engenders in me an emotion of thankfulness. When a gift teeters in the balance, or seems to for a time, fear and prayer are my immediate reactions. If the gift is spared, my relief mingles with thankfulness to God, creating an emotional state that is generally even more intense than my thankfulness for a new blessing.

However, I have been unable to manufacture any passable facsimile of this emotion in my day-to-day life. I can remind myself that I should, and must, be thankful, but this is an intellectual knowledge, not an emotional one.

When a person does something for me it is easier to feel thankful. I am able to relate to a fellow human being, to visualize myself as the other and recognize the effort that the person has put in, with the knowledge that what the person has done for me was not required. I can imagine what it would be like to be the giver; I know that the gift I was given was inconvenient, or time-consuming, or difficult to give.

With God, it is not so. I cannot put myself in His position. I cannot imagine any “effort” on His part. There is a total disconnect between the state of the giver and the state of the receiver, making it far more difficult to create an emotion of thankfulness.

It is also easier to express gratitude to human beings. When a person goes out of his/her way to do something for you, even just a verbal expression of thanks can have a profound effect on both the giver and the receiver. Often, some sort of reciprocal act also communicates one’s appreciation. The very process of acting allows the receiver to internalize his gratitude.

With God, however, it is different. Yes, in the time of the BHMK there were (and will be, according to many opinions) korbanot, particularly the korban Todah, an active manifestation of thanks. And nowadays there are the hoda’ah sections of tefillah, verbal declarations of thanks for our blessings and the miracles that God performs for us daily. But although saying these prayers can sometimes have a minimal positive effect on my emotional state, it rarely creates the powerful emotion that I seek.

When dealing with God, my thanks can receive no tangible reception; I can see no effect of my words, and I know that my expression of gratitude cannot benefit the subject of it. In this case, the only entity who truly benefits is myself. This makes the thanks I utter echo endlessly in my own ears, yet still it rings hollow.

I do not know the solution to my problem. I do not know how to inspire or create an emotion of thankfulness to permeate my everyday life. I know only that I should feel thankful, that I want to feel thankful, and that, in the core of my being, I am thankful. I only hope that I can find a way to tap into some hidden reserve of emotion that will allow me to experience thankfulness in a way that is conscious and true.

Thursday, December 13, 2007

Do We Create God In Our Image?

We are the devout, the believers. We follow God’s laws to the best of our abilities, we center our lives around what we believe He desires, we address Him daily in our prayers. Yet, do you and I really worship the same deity?

Orthodox Judaism dictates belief in a single God—a God whose oneness transcends any unity we can conceive of; whose omniscience is undisputed; whose incorporeality puts Him beyond the scope of our imaginations. Yet we attempt to have a relationship with this God—because we wish it and because we believe that He wishes it. And so we try, futile as it may be, to figure out what He wants us to do on a daily basis, to turn to Him for answers.

The problem is this: as humans we are so limited, our perspectives so narrow—is it really God we relate to, or merely our own personal conception of Him? As limited humans, we know only ourselves. We relate to others, but we can never really enter into anyone’s consciousness but our own. As Rav Soloveitchik explains in his essay Confrontation: “Each [person] exists in a singular manner, completely absorbed in his individual awareness which is egocentric and exclusive. The sun of existence rises with the birth of one's self awareness and sets with its termination. It is beyond the experiential power of an individual to visualize an existence preceding or following his.”

Because we are so innately self-centered, it naturally follows that our view of God is affected by our own personal outlook and biases. The way I view God differs from the way you view Him, because I view the world differently than you do. Even two people within the same sub-sub-group of Orthodox Judaism will not view God in the same way, because each person is, inescapably, an individual.

I was speaking to a few friends the other day, remembering the ways in which we used to picture God when we were very young. We were all brought up with the idea of one God who knew everything, we were probably taught very similar things in school—yet the differences between the ways we conceived of Him were easily discerned. One friend remembered thinking of a tall, Rabbinic looking figure with a long white beard. Another friend simply visualized a large, magnificent throne to pray to. And yet another (slightly odd) friend imagined a giant cucumber in the sky (no, I’m not kidding). Personally, I don’t remember creating a visual image, but no doubt I had my own unique ideas nevertheless.

In children, these differences are obvious, because they conceive of God in a very physical way. We can easily recognize the contrasts between the various pictures we drew in our minds. As mature adults, though, are we so different? Perhaps we are no longer thinking of old men or thrones or cucumbers, but we do imagine a God that fits with our own personal ideas. Is He a friend to confide secrets to, or a stern taskmaster who punishes? A regal king or a familiar father? Theologically we’d probably answer “all of the above,” but when we talk to Him, who are we really talking to?

This presents a serious danger. If everyone has a tailor-made God, where is the line between God and self? When I talk to Hashem, who is to say that in reality I am not merely talking to myself? This is a frightening thought. If I have created God in my own image, then what do I have, really? I have an imagined relationship with something of my own creation, not with the true King. Yet, is this an avoidable phenomenon? It is truly a dilemma, and one that I think we all must recognize.

It occurred to me that is this issue that makes the prescribed words of tefillah so important. Many people (including myself) are often frustrated by the repetitiveness of tefillah--the same words, three times a day, over and over and over. Where is the originality? Where is the individuality? How is one supposed to feel anything when we are forced to endlessly repeat? As valid as these concerns are, individualized prayer presents a hazard that is even more pressing. Without a prescribed formula for prayer, people would simply tailor their words to their own personal God, and could very soon lose sight of the greater concept of God entirely. The words of tefillah force us to think of God in a certain way, reminding us of true ideas about God, preventing us from praying to a God wholly of our own imagination and conception. Though it does not eliminate the philosophical dilemma entirely, by any means, it is one tool that the system provides in order to help us grapple with this complex issue.

Orthodox Judaism dictates belief in a single God—a God whose oneness transcends any unity we can conceive of; whose omniscience is undisputed; whose incorporeality puts Him beyond the scope of our imaginations. Yet we attempt to have a relationship with this God—because we wish it and because we believe that He wishes it. And so we try, futile as it may be, to figure out what He wants us to do on a daily basis, to turn to Him for answers.

The problem is this: as humans we are so limited, our perspectives so narrow—is it really God we relate to, or merely our own personal conception of Him? As limited humans, we know only ourselves. We relate to others, but we can never really enter into anyone’s consciousness but our own. As Rav Soloveitchik explains in his essay Confrontation: “Each [person] exists in a singular manner, completely absorbed in his individual awareness which is egocentric and exclusive. The sun of existence rises with the birth of one's self awareness and sets with its termination. It is beyond the experiential power of an individual to visualize an existence preceding or following his.”

Because we are so innately self-centered, it naturally follows that our view of God is affected by our own personal outlook and biases. The way I view God differs from the way you view Him, because I view the world differently than you do. Even two people within the same sub-sub-group of Orthodox Judaism will not view God in the same way, because each person is, inescapably, an individual.

I was speaking to a few friends the other day, remembering the ways in which we used to picture God when we were very young. We were all brought up with the idea of one God who knew everything, we were probably taught very similar things in school—yet the differences between the ways we conceived of Him were easily discerned. One friend remembered thinking of a tall, Rabbinic looking figure with a long white beard. Another friend simply visualized a large, magnificent throne to pray to. And yet another (slightly odd) friend imagined a giant cucumber in the sky (no, I’m not kidding). Personally, I don’t remember creating a visual image, but no doubt I had my own unique ideas nevertheless.

In children, these differences are obvious, because they conceive of God in a very physical way. We can easily recognize the contrasts between the various pictures we drew in our minds. As mature adults, though, are we so different? Perhaps we are no longer thinking of old men or thrones or cucumbers, but we do imagine a God that fits with our own personal ideas. Is He a friend to confide secrets to, or a stern taskmaster who punishes? A regal king or a familiar father? Theologically we’d probably answer “all of the above,” but when we talk to Him, who are we really talking to?

This presents a serious danger. If everyone has a tailor-made God, where is the line between God and self? When I talk to Hashem, who is to say that in reality I am not merely talking to myself? This is a frightening thought. If I have created God in my own image, then what do I have, really? I have an imagined relationship with something of my own creation, not with the true King. Yet, is this an avoidable phenomenon? It is truly a dilemma, and one that I think we all must recognize.

It occurred to me that is this issue that makes the prescribed words of tefillah so important. Many people (including myself) are often frustrated by the repetitiveness of tefillah--the same words, three times a day, over and over and over. Where is the originality? Where is the individuality? How is one supposed to feel anything when we are forced to endlessly repeat? As valid as these concerns are, individualized prayer presents a hazard that is even more pressing. Without a prescribed formula for prayer, people would simply tailor their words to their own personal God, and could very soon lose sight of the greater concept of God entirely. The words of tefillah force us to think of God in a certain way, reminding us of true ideas about God, preventing us from praying to a God wholly of our own imagination and conception. Though it does not eliminate the philosophical dilemma entirely, by any means, it is one tool that the system provides in order to help us grapple with this complex issue.

Labels:

discussion,

perspective,

philosophy,

prayer,

questions,

the Rav

Friday, September 21, 2007

Trembling

I wish I had something truly insightful and original to post here, but lately my thoughts, though very occupied with matters of din and rachamim and teshuva and tefilah and olam haba and olam hazeh, have been more often confused than coherent. So I will spare you the angst.

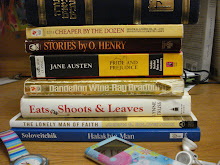

One thought on Yom Kippur, that I heard from Rabbi Hanoch Teller during my year in Israel: people often complain that it is impossible to focus on tefillah while fasting. How are we supposed to concentrate our thoughts to heaven if our stomachs are rumbling? Rabbi Teller counters: haven't you ever been reading, and been so engrossed in the book that the hours fly by, until you finish, only to realize that your neck is sore, that it is 3:00 am, and that you are super hungry? (I, for one, know that this has happened to me.) It is possible to get so engrossed in a task that everything else gets shut out, even basic physical concerns. If we were able to immerse ourselves entirely in our tefillos, we would not even notice our hunger. Though very few people are actually on that level, even I have experienced it to some degree, if only for moments instead of hours. So on Yom Kippur, when my stomach starts to distract me, I redouble my efforts to focus on what I am saying, on what weighs in the balance and what I am asking for.

I wish everyone a gmar chasimah tova--may your tefilos be answered, and may we all be sealed for another year of life and happiness.

One thought on Yom Kippur, that I heard from Rabbi Hanoch Teller during my year in Israel: people often complain that it is impossible to focus on tefillah while fasting. How are we supposed to concentrate our thoughts to heaven if our stomachs are rumbling? Rabbi Teller counters: haven't you ever been reading, and been so engrossed in the book that the hours fly by, until you finish, only to realize that your neck is sore, that it is 3:00 am, and that you are super hungry? (I, for one, know that this has happened to me.) It is possible to get so engrossed in a task that everything else gets shut out, even basic physical concerns. If we were able to immerse ourselves entirely in our tefillos, we would not even notice our hunger. Though very few people are actually on that level, even I have experienced it to some degree, if only for moments instead of hours. So on Yom Kippur, when my stomach starts to distract me, I redouble my efforts to focus on what I am saying, on what weighs in the balance and what I am asking for.

I wish everyone a gmar chasimah tova--may your tefilos be answered, and may we all be sealed for another year of life and happiness.

Friday, December 29, 2006

My Tefillah

Hashem, please give me strength. I know You have a plan for me; please reveal it to me in the right time--and in the meantime, help me understand that there is a reason for whatever I endure. Help me to truly believe that everything is for the good. Help me to feel Your presence in my life every day, to feel Your hand guiding me and supporting me. Help me to grow from my hardships, to pass the tests You give me, to use them to become closer to You. Help me to be thankful every day for the thousands and thousands of blessings you shower upon me at every moment. Help me to learn from past mistakes, and to grow from them. Help me to treat people the way that they deserve to be treated, to be sensitive to their needs, and never to wound another with my words or actions. Help me spread Your Torah and mitzvot to those of Your people who are unaware of their glory. May my tefilot always be sincere, and may they reach Your heavenly throne. I love You, for you are my Father; I revere You, for you are my King; to You I owe my life and all that is good.

May the words of my mouth and the desires of my heart find favor before you, Hashem, my Rock and my Redeemer.

May the words of my mouth and the desires of my heart find favor before you, Hashem, my Rock and my Redeemer.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)