Thursday, January 29, 2009

Questioning A Passion

If there is something I love to do, but it is not deeply meaningful in an obvious way, do I have the right to pursue it? Is it right to devote huge amounts of time and energy to an activity simply because I enjoy it, because it excites me in a unique way, because it is a side of myself I don't often get to hone? Or is succumbing to such a passion merely a weakness, if that activity is not as significant as other things I could be doing with my time?

What is the point of hobbies, in general? Is there a point? Are they a waste of time?

Am I selfish for wanting this so much, despite the inevitable sacrifices?

Monday, September 08, 2008

Does God Love You?

In a recent conversation on the topic of emotional connection to God, a friend raised the idea of focusing on God’s love as a means to achieving reciprocal emotion. In other words, by reminding yourself that God loves you and by focusing on all the good things He has given you as a result of His love, you can internalize the fact that He loves you and, as the theory goes, you will then eventually love Him back.

My friend also mentioned a Rosh Yeshiva whose motto is “Do you know Hashem loves you?” and who will ask children, “Who loves you the most in the world?” If a child answers, “My parents,” he will respond, “No, Hashem loves you even more!”

This idea does not sit well with me. To my ears it sounds far more like the Christian mantra “Jesus loves you” than like an authentically Jewish approach.

My question is: does God really ‘love’ us?

Obviously, we believe that God created the world and the Torah for our benefit—clearly it could not be for His own, since He has no needs. However, is this concept of a personal, emotional love a part of our weltanschauung? Certainly we are obligated to love God, but does He love us?

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Confronting the Questions

Over shabbos, a close family friend raised an interesting issue. A discussion of the parsha somehow led into speculation about some of the modern historical, scientific, and anthropological challenges to certain accounts in the Torah.

For instance, let’s say you believe that it has been 5,768 years since Adam HaRishon spoke. This assumes that you adopt the more scientifically compatible position that a “day” of creation really means a stage, and that each day could have lasted thousands of years, so that 5768 is not the age of the universe, but rather the age of humanity. Okay, so let’s say you accept that. Still, modern anthropology tells us that human beings have existed for much much longer than that. How do we resolve this contradiction?

The point our friend was making is that within the religious Jewish world very little attention is paid to such questions. They are generally ignored, or dismissed as unimportant or uninteresting. This disturbs him, because he feels that, especially within the Modern Orthodox community which professes to unite the world of secular knowledge with that of religious scholarship, these issues should not be swept under the rug.

And my thoughts, on a personal level, are as follows: as many of you know, I am interested primarily in the humanities and the arts. I love literature, writing, philosophy, music, drama. I do not like math. I do not like science. I often find history somewhat dry. This may be a failing. This may just be my personality.

Regardless, I tend to spend my time studying and pursuing the areas that I find compelling. This means that I know very little about science, very little about anthropology. Most of the questions and challenges to religion that exist in those areas are foreign to me simply because I do not know enough to even realize that they exist. Our friend argued that this approach is intellectually dishonest. And I wonder: is it?

Even if I studied those areas and began to comprehend some of the problems and seeming contradictions that exist, even if I encountered a question with no apparent answer, would I give up my faith?

I honestly think not. I know that there are questions that are not easily resolved. I know that I certainly do not have all the answers. But I don’t feel that I have to. The things that form the basis of my faith are unrelated to the Torah’s apparent scientific accuracy, or lack thereof.

So I feel justified in not pursuing these issues. I’m, frankly, not all that interested in these areas, and don’t feel compelled to research and discover the questions I know are out there.

Is this a mistake? Is it intellectually dishonest? Any thoughts?

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

The Limits of Empathy

Very few people will brush off the news without even a second thought. Even fewer (probably none) will feel the pain like someone who was directly affected. But between these two extremes, what is your reaction, and what do you believe the proper reaction should be? Is it correct to feel pain, and if so, to what extent? Should one encourage feelings of pain and sadness, or try to dispel them?

There are, as I see it, pros and cons to each side. One might argue that you should encourage and experience sensations of grief: this is empathy, feeling for someone else, a compassionate human quality. When you suffer, I suffer, because we are all intrinsically connected.

However, on the other side, if I allow myself to grieve, if I dwell on the tragedy, cry, and feel pain, where do I draw the line? At what point do I distract myself from these thoughts, or allow myself to be distracted? At what point does my grief for people unknown become excessive, detracting from my ability to do other things, to be productive, to live my own life? Is it really right for me to be sad and depressed, even for just a number of hours, because of something that didn’t happen to me, and that only hurts me because I allow it to?

Sunday, April 13, 2008

"Which Way Is Up?" Revisited

I’ve always been a thoughtful person, someone who thinks about what she does and why she does it. I’ve come to where I am in life through much reflection and by drawing my own conclusions. And I acknowledge that, young as I am, my process of development is nowhere near its end. In fact, I hope and expect to be thinking and growing for as long as I am allowed the privilege of living in this world.

I am also a strong believer in the multiplicity of perspectives that exist within Torah Judaism. As one of my Rebbeim in seminary put it: “Gray is my hashkafa.” The right choice is not always clear; every decision comes with sacrifices, every chumra with a kulah. Because of the existence of endless nuance, every choice must be evaluated on its own; the answer perpetually sought, rarely crystal clear.

For all of these reasons, I chose “Which Way” to represent myself and my blog—symbolic of my constant search for the truest path, a search I know will never be concluded.

However, for most of my blog’s lifespan, its title has not necessarily reflected the content of its posts. Though it was an accurate depiction of a crucial aspect of its author’s philosophy, the blog itself was not (primarily) utilized as a medium to further that mission. Though I’ve touched on philosophical topics, most of those posts did not generate much further discussion—and I’ve also spent lots of blogspace regaling readers with tales of procrastination and adventures (in NYC, London, Israel, and elsewhere), as well as musings on writing, chagim, and lots of other randomness.

Over the past number of months, I’ve found myself thinking even more than usual. I’ve come back to philosophical questions I might have considered “settled” before, and have pondered many more that had never occurred to me. More than ever, I feel myself seeking discussion and debate. Not just about the ‘big’ questions of life and religion, but also about more specific topics that occur to me at random.

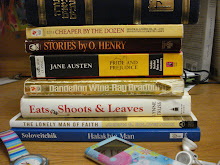

At the beginning of The Lonely Man of Faith, the Rav writes, “Knowledge in general and self-knowledge in particular are gained not only from discovering logical answers but also from formulating logical, even though unanswerable, questions.” Asking questions is a crucial exercise, even when no one conclusive answer is reached.

So when questions occur to me, I want discussion, above all. I thank God that I am blessed with several circles of wonderful and intelligent friends, but often I want more than a single perspective can offer. I want a discussion that extends beyond one, two, three, people, into a larger circle of diverging viewpoints.

And so I’ve found myself turning to my blog as a place to ask questions, and hopefully generate discussion. Within the past months, the comments on these posts are the closest my blog has come to providing what I’m looking for, but I have about six or seven posts—philosophical issues or questions—running through my head that I’d like to write up and discuss. I cannot promise that I will do so, and I’m not planning to start writing every day (far from it!), but I would love to create a place for meaningful thought and discussion—and none of that can happen without you, the readers and commenters.

So welcome all—I encourage you to add your unique perspectives to every post, to make this blog a place for questions, for Truth-seeking, and for knowledge in general and self-knowledge in particular.

Monday, April 07, 2008

God's Plan and Free Will

And even assuming that He is guiding each step of our lives, how much room is there for us to mess it up? We have free will, don’t we? Doesn’t that mean that despite Hashem’s best laid plans, we have the ability to make mistakes and ruin it all? What if, presented with that golden opportunity, we turn it down? We are human, we are flawed, we cannot always see what the correct choice is, so we stumble along, doing out best. But what if we are wrong? What if that chance is lost?

Thursday, December 13, 2007

Do We Create God In Our Image?

Orthodox Judaism dictates belief in a single God—a God whose oneness transcends any unity we can conceive of; whose omniscience is undisputed; whose incorporeality puts Him beyond the scope of our imaginations. Yet we attempt to have a relationship with this God—because we wish it and because we believe that He wishes it. And so we try, futile as it may be, to figure out what He wants us to do on a daily basis, to turn to Him for answers.

The problem is this: as humans we are so limited, our perspectives so narrow—is it really God we relate to, or merely our own personal conception of Him? As limited humans, we know only ourselves. We relate to others, but we can never really enter into anyone’s consciousness but our own. As Rav Soloveitchik explains in his essay Confrontation: “Each [person] exists in a singular manner, completely absorbed in his individual awareness which is egocentric and exclusive. The sun of existence rises with the birth of one's self awareness and sets with its termination. It is beyond the experiential power of an individual to visualize an existence preceding or following his.”

Because we are so innately self-centered, it naturally follows that our view of God is affected by our own personal outlook and biases. The way I view God differs from the way you view Him, because I view the world differently than you do. Even two people within the same sub-sub-group of Orthodox Judaism will not view God in the same way, because each person is, inescapably, an individual.

I was speaking to a few friends the other day, remembering the ways in which we used to picture God when we were very young. We were all brought up with the idea of one God who knew everything, we were probably taught very similar things in school—yet the differences between the ways we conceived of Him were easily discerned. One friend remembered thinking of a tall, Rabbinic looking figure with a long white beard. Another friend simply visualized a large, magnificent throne to pray to. And yet another (slightly odd) friend imagined a giant cucumber in the sky (no, I’m not kidding). Personally, I don’t remember creating a visual image, but no doubt I had my own unique ideas nevertheless.

In children, these differences are obvious, because they conceive of God in a very physical way. We can easily recognize the contrasts between the various pictures we drew in our minds. As mature adults, though, are we so different? Perhaps we are no longer thinking of old men or thrones or cucumbers, but we do imagine a God that fits with our own personal ideas. Is He a friend to confide secrets to, or a stern taskmaster who punishes? A regal king or a familiar father? Theologically we’d probably answer “all of the above,” but when we talk to Him, who are we really talking to?

This presents a serious danger. If everyone has a tailor-made God, where is the line between God and self? When I talk to Hashem, who is to say that in reality I am not merely talking to myself? This is a frightening thought. If I have created God in my own image, then what do I have, really? I have an imagined relationship with something of my own creation, not with the true King. Yet, is this an avoidable phenomenon? It is truly a dilemma, and one that I think we all must recognize.

It occurred to me that is this issue that makes the prescribed words of tefillah so important. Many people (including myself) are often frustrated by the repetitiveness of tefillah--the same words, three times a day, over and over and over. Where is the originality? Where is the individuality? How is one supposed to feel anything when we are forced to endlessly repeat? As valid as these concerns are, individualized prayer presents a hazard that is even more pressing. Without a prescribed formula for prayer, people would simply tailor their words to their own personal God, and could very soon lose sight of the greater concept of God entirely. The words of tefillah force us to think of God in a certain way, reminding us of true ideas about God, preventing us from praying to a God wholly of our own imagination and conception. Though it does not eliminate the philosophical dilemma entirely, by any means, it is one tool that the system provides in order to help us grapple with this complex issue.

Friday, November 16, 2007

Which Would You Choose?

A few weeks ago, someone asked me a question which put me in a similar position. I gave my own answer, but I’d be interested to hear some other perspectives. The situation is this:

If you had the choice between being mekareiv 10,000 people who will then be “frum” to a normal halachic standard, or being mekareiv one person who will go on to become the gadol hador—which would you choose?

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

And The Answer Is...

Lately I’ve noticed a strange phenomenon. When people give divrei Torah, they usually begin with a question. (No, that’s not the strange part.) Many will then continue, “And the answer is…” Whenever I hear this, it jars me. So I began to think: what about this simple phrase bothers me so much?

Lately I’ve noticed a strange phenomenon. When people give divrei Torah, they usually begin with a question. (No, that’s not the strange part.) Many will then continue, “And the answer is…” Whenever I hear this, it jars me. So I began to think: what about this simple phrase bothers me so much? On the most basic level, the phrase implies that the answer given is the only answer to the question (by saying “the answer is…” instead of “Rashi’s answer is…” or “Rav Willig answers that…”). Saying “the answer” is a sort of conceit—and also, to me, comes off as uneducated.

When teaching a child Torah, it is common (and understandable) to pose a simple question, and then to give one answer as the answer. I remember learning this way in fourth grade, and being so proud to show off my knowledge to my parents. I had a question, and I knew the answer. Period. Children see things only in black and white—they cannot grasp the idea that there could be more than one correct answer.

Adults, however, understand the existence of multiple answers to Torah questions. The concept of shivim panim l’Torah is a fundamental component of our system. It is only those with some degree of intellectual sophistication who can understand that life is comprised mainly of shades of gray—and that Torah reflects this in the multiplicity of its perspectives. This idea is manifested throughout the entire system of Orthodoxy. It allows one to understand that there are many different valid derachim within halachic Judaism, and prevents belief in one’s own way to the exclusion of every other.

Religious fanaticism is the easy way out. It’s much easier to believe that there is only one right way, and that everyone else is wrong. It makes life simpler. It is also a childish and dangerous way of seeing the world. The basis for so much of what we believe rests in the idea that there can be more than one right answer.

Though “And the answer is…” seems but a harmless phrase, its philosophical ramifications are more complex and far-reaching than one might originally surmise. Though I don’t assume that anyone who uses that phrase has serious philosophical issues (since I understand that yes, it is only a phrase, and I shouldn’t read into it too much), the idea that it implies is deeply problematic.

Sunday, April 15, 2007

Why I Don't Read Holocaust Books

I have lived a perfect life, a life entirely free from intense suffering. Sure, I have known people—young people, good people—who have suffered from terrible diseases, from impossible hardship. But these people have not been the people closest to me, so these tragedies have not touched me in the most personal way. My faith is strong—but who am I to talk, I whose faith has never been tested?

Don’t get me wrong, I am not asking for a test. I’m not asking for a tragedy, chas v’shalom. But I fear. I have lived a life without trial, yet I am imperfect. If, given every gift that Hashem can possibly offer, I still am unable to serve Him perfectly (in fact, far from it), where would I be if something terrible happened?

And that’s where the Holocaust books come in. My whole life, I never read any (with the exception of Elie Wiesel’s Night, which I had to read for school). My philosophy, right or wrong, has always been: why make yourself sad on purpose? Besides, I am extremely squeamish, and the details of Holocaust tales have always been too much for me to handle.

Now, a junior in college, one of my classes has required me to read a book called The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million by Daniel Mendelsohn. The author tells his own tale, a man searching for the stories of six of his ancestors who were killed by the Nazis. He travels from the Ukraine, to Australia, to Israel, seeking out his history. His saga is interspersed with comparisons to stories in Sefer Bereishit, as elucidated by Rashi and a modern commentator named Friedman. The author himself is not Orthodox—he was brought up vaguely Reform, and although since then he has ‘discovered’ much of his heritage, the impression I have gotten is that he still takes a secular approach to the validity of the Torah. The book is long, 500 pages, and I am only halfway through. Though it is slow reading, I have, for the most part, enjoyed its intricate rambling and frequent keen insights.

But reading about some of the horrors of the Holocaust, and only just the horrors that occurred to the population of a tiny town called Bolechow, has also frightened me immensely. Reading the book for long periods of time, I feel sucked into a world I am afraid of. The way that Hashem allowed people, Jewish people, religious people, to be treated makes me forget, momentarily, that He is just. When I hear that the Rabbis suffered most—how a Rabbi, his eyes cut out, was forced to dance naked with a woman for the officers’ amusement, I wonder—how? Why?

Yes, I had heard about the evils of the Holocaust before. I had heard of the slaughter, but rarely in such vivid detail. Six million is not just a number. Six million are people, each with an individual story. When I hear the story of a single death I am sickened—multiply that horror by six million, and what happens? I cannot even fathom it.

And that, that is why I do not read Holocaust books. Because yes, it is important to be aware of our history. Yes, it is bad to close your eyes to reality. But I am not as strong as I should be. Hashem has not tested my faith, He has not put me in their shoes. Maybe, in a tough situation, I’d find my hidden strength. I’d like to think I would. But their tests are not mine, and reading about them will not make them mine—it will only confuse me.

As a close friend said, “I’d rather not shred myself up into little tiny pieces just to see if the pieces can come back together when I close the book.”

Sunday, February 25, 2007

The Value of Playing Devil's Advocate

In addition to blog-related topics of conversation, we had quite a few other deep and fascinating (and lengthy) discussions. One of these related to whether it is necessary to acknowledge the validity of approaches that conflict with our own, and whether by doing so one is crushing youthful idealism.

I shall not even attempt to recap the majority of the conversation, but for me, the bottom line was that it is absolutely imperative to try to understand the point of view of those with whom we disagree, for two main reasons. One is that, though idealism is wonderful, it is impractical to refuse to see how the world functions (even if you disagree with the methods by which it does). Idealists are the only ones who will ever be able to affect change, and if they stay in lala land and never open their eyes to the real world and to points of view that differ from their own, how are they going to do anything? If you simply say “the other side is garbage” and dismiss it, no one will listen to anything you have to say. You need to understand the other side in order to argue against it.

Furthermore…and I think even more importantly...it is crucial to understand that there is another perspective. That even though you may disagree with that perspective, it is an approach. It is valid. People who hold that approach are valid, and it is not right to harbor dislike and animosity towards them. We have to understand them in order to love them, to promote ahavas Yisroel. For me, this is the bottom line. Love your fellow Jew. The End.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Teshuva

For obvious reasons, this topic has been cropping up a lot lately. Though Yom Kippur is over, some random thoughts about teshuva:

I had a discussion over shabbos about the hardest part of teshuva. We concluded that the hardest part is also one of the most integral components of ensuring that the chayt doesn’t occur again. When a person sins, it is usually not merely for the thrill of sinning, not done simply to rebel against G-d (if it is, you have a much bigger problem). Usually, a sin is done because a person believes that it will benefit him in some way. For example, you steal an i-pod because you want to enjoy use of that i-pod. Or, you embarrass your friend because in some way that makes you feel superior. So the issue is this: how do you retroactively get rid of the pleasure that you got from your sin? How do you force yourself to realize that in reality you did not benefit at all—that in fact, you lost exponentially more than you gained? Though you may have returned the i-pod or apologized to your friend, you still have a memory of the enjoyment that you got from the sin. How do you change that memory from a pleasant one to one that repulses you at the very thought? If a person is successful in this area, I think it is virtually certain that the sin will not occur again, because it means that he has realized that there is nothing to gain from the sin, and everything to lose. But unfortunately, it is really hard to do. Any suggestions about how to accomplish this feat?

This topic also leads in to another discussion that I had on shabbos at the residence of a very illustrious j-blogger (who I was privileged to finally meet properly). The question was raised: would it be a good thing if, as part of the teshuva process, the memory of your sin would be erased? After confessing your sin and thoroughly regretting it, all memory that the sin occurred would disappear. On one hand, this would be a solution to the problem I described above—if you have no memory of the sin, you can’t remember the pleasure you got from it. Yet, I argued that overall it would not be a good thing. If you have no recollection of your sin and your consequent regret, what’s to keep you from repeating your mistake? The fact that you sinned in a specific area must mean that you have a yetzer hara for that sin—that for some reason you are compelled to do it. The thing that will keep you from doing it again is the memory that you tried it, and then realized how wrong it was—and that it was eminently not worth it. Without memory, you have no experience to learn from, so you will just keep falling into the same traps.