Over shabbos, a close family friend raised an interesting issue. A discussion of the parsha somehow led into speculation about some of the modern historical, scientific, and anthropological challenges to certain accounts in the Torah.

For instance, let’s say you believe that it has been 5,768 years since Adam HaRishon spoke. This assumes that you adopt the more scientifically compatible position that a “day” of creation really means a stage, and that each day could have lasted thousands of years, so that 5768 is not the age of the universe, but rather the age of humanity. Okay, so let’s say you accept that. Still, modern anthropology tells us that human beings have existed for much much longer than that. How do we resolve this contradiction?

The point our friend was making is that within the religious Jewish world very little attention is paid to such questions. They are generally ignored, or dismissed as unimportant or uninteresting. This disturbs him, because he feels that, especially within the Modern Orthodox community which professes to unite the world of secular knowledge with that of religious scholarship, these issues should not be swept under the rug.

And my thoughts, on a personal level, are as follows: as many of you know, I am interested primarily in the humanities and the arts. I love literature, writing, philosophy, music, drama. I do not like math. I do not like science. I often find history somewhat dry. This may be a failing. This may just be my personality.

Regardless, I tend to spend my time studying and pursuing the areas that I find compelling. This means that I know very little about science, very little about anthropology. Most of the questions and challenges to religion that exist in those areas are foreign to me simply because I do not know enough to even realize that they exist. Our friend argued that this approach is intellectually dishonest. And I wonder: is it?

Even if I studied those areas and began to comprehend some of the problems and seeming contradictions that exist, even if I encountered a question with no apparent answer, would I give up my faith?

I honestly think not. I know that there are questions that are not easily resolved. I know that I certainly do not have all the answers. But I don’t feel that I have to. The things that form the basis of my faith are unrelated to the Torah’s apparent scientific accuracy, or lack thereof.

So I feel justified in not pursuing these issues. I’m, frankly, not all that interested in these areas, and don’t feel compelled to research and discover the questions I know are out there.

Is this a mistake? Is it intellectually dishonest? Any thoughts?

17 comments:

You're of the "sweep it under the rug" philosophy, I see. Big, obvious gaps between science/history and Torah may not bother you but they should be confronted--I think they probably have been, for the most part, but certainly we need to say a problem is a problem, and examine carefully our desires to just ignore them. Did Neanderthal man exist at the same time as Adam ha Rishon? Was Mr. Neanderthal a "human?" I think we do have to search for answers, and be honest.

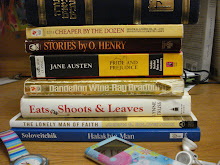

In chapter 1 of LMoF, RYBS notes a set of such real and unavoidable issues: "the problem of the Biblical doctrine of creation vis-a-vis the scientific story of evolution at both the cosmic and the organic levels... the confrontation of the mechanistic interpretation of the human mind with the Biblical-spiritual concept of man... the impossibility of fitting the mystery of revelation into the framework of historical empiricism... the theories of Biblical criticism which contradict the very foundations upon which the sanctity and integrity of the Scriptures rest." However, despite his recognition of the issues, he notes that these problems have never seriously troubled him, so that you seem to be on defended intellectual territory.

At the risk of inserting my own ideas into the philosophy of RYBS, it seems to me that his decision to de-emphasize these questions is a form of intellectual triage. We don't have answers to these questions that are entirely satisfying, and may still be quite far from arriving at them. However, the answers are non-essential to our purpose in this world. On the other hand, there are questions which are absolutely essential, to the extent that if one does not answer them, one may end up leaving this world with nothing to show for it. Were we to be granted an infinite number of years of thought, there would be no problem in maintaining a focus on these questions in the interest of collecting whatever small gains we are able to, but in the absence of such, we have to unfortunately relegate them to Shabbos discussions and blog posts.

R' Aviner has a good comment on the subject - Gil posted it a while back. It's worth reading what he wrote.

Wow. I can totally relate to what you wrote in this post.

These things just don't bother me. I don't worry about these questions, they don't affect my emunah, and I am happy to accept really simplified answers that make sense to me.

I end up asking myself this as well: is there a need for me to go out and seek the answers to these types of questions if they don't bother me to begin with? Is it bad if I don't feel like I need to pursue it?

So what's the question here,,,Is ignorance bliss? Is cognitive dissonance bliss?

I don't mean those in a condescending way, I am really asking.

The best way to reach the conlcusion that intellectual honesty may be discarded is by using intellectual honety--and not merely emotion--to reach that conclusion and justify it.

Yes, I realize that this sounds circular, but somehow I think it makes sense.

Also, perhaps you can ask yourself whether you have the proper kowledge tools in your present age to actually take on the challenges. I certainly don't feel equipped to consider the challenges of science, history, and the DH most of the time. It's not a rejection of intellectual honesty per se. It's just pushing it off until later--and vigilantly continuing to study both Torah and other things in the interim.

Josh - thanks for pointing me to the quote in LMoF...though I don't know if I really agree with your analysis of RYBS's thought process.

In context, the quote seems to simply dismiss the issues altogether as something he has "never been seriously troubled by." He uses his lack of perplexity about these issues to contrast with how he feels regarding the dilemma that he examines in the essay: "...while theoretical oppositions and dichotomies have never tormented my thoughts, I could not shake off the disquieting feeling that the practical role of the man of faith within modern society is a very difficult, indeed, a paradoxical one."

To me, this quote indicates not that lack of time forces him to choose one troublesome issue over others, but that the former simply do not bother him while the latter does--perhaps because science is not his sphere, but philosophy is.

Incidentally, this is very similar to how I feel about these issues, so if I'm right about my evaluation of his words, I do feel more secure about my position. Thanks for pointing me to it.

G - No, I'm not asking whether ignorance or cognitive dissonance is bliss. I'm asking whether a person who attempts intellectual honesty can reasonably maintain ignorance regarding certain issues if she is fairly certain that even knowledge of those issues will not unseat her belief. It is not possible for any one person to be knowledgeable about everything, so I am asking whether this is a topic that I may reasonably choose not to spend my time on, or whether it something that, in order to be fair and honest, I must prioritize over other things I might prefer to learn.

If you were an anthropologist/geologist, I'd say that ignoring anthropological/geological theories that do not seem to mesh with your belief system is probably intellectually dishonest. But if you don't study the science to begin with, why would you delve into a tangent of the science?

(Aside-"popular" science bothers me quite a bit, but laymen debating how fine points of subtopics of complex scientific theory may or may not support or challenge Torah drives me absolutely nuts. If a person isn't prepared to devote a lot of time and focus to understanding the scientific issues to begin with, why on earth would their debates on abovementioned scientific issues have any solid intellectual value?)

BTW, you do know that I'm M.R., right? I'm just signed into gmail right now and I don't feel like signing out.

Uninformed opinion follows: In view of Torah, I think the science is dubious. If a "day" is a "millenium" and day requires night (as opposites), then why should the physical world not contain a reverse of the time expansion which you write explains the Genesis story?

Slighty more informed opinion follows: I remember learning how old objects are dated. My awe for this world includes asking why our rules of physics should hold from one instance in time to the next. Well, who says physics is true?

The science institution accepts postulates which are falsifiable. This means it is possible for rules of physics to be shown not-false in so many experiments that they are taken for granted--but for them to fail every time the experiment is not given our attention.

I don't mean to say our planet was created with fossils embedded; I am more inclined to believe that our methods of dating old, never seen before objects are not as accurate as they are believed to be. If the length of a "day" may change over time, then why must another property of the physical world--radioactive half-life--remain constant?

Josh0 - In my original discussion of the issue last shabbos, I actually brought up a similar point. As I have mentioned, I know very little about the science involved in any of this. However, I pointed out that over the years scientists have believed staunchly in many things that were later discovered to be scientifically incorrect. How do we know that in fifty years the science we accept today won't be outdated and replaced with new theories?

whether a person who attempts intellectual honesty can reasonably maintain ignorance regarding certain issues if she is fairly certain that even knowledge of those issues will not unseat her belief.

If so then what will be the value/purpose in that knowledge for said person?

whether this is a topic that I may reasonably choose not to spend my time on, or whether it something that, in order to be fair and honest, I must prioritize over other things I might prefer to learn.

Which one will make you more happy?

How do we know that in fifty years the science we accept today won't be outdated and replaced with new theories?

That theory doesn't leave a whole lot left for study.

Basically just math and certain parts of the arts.

G - Do you think happiness should be a factor?

Yes, a major one as I commented above.

May I ask why? If the question at hand is intellectual honesty, where does happiness come into play?

Don't get me wrong, I'm not dismissing it as unimportant--I'm just wondering if you could clarify how it connects to this issue in your mind.

Post a Comment